The GFNY Mont Ventoux sportive

Broleur attempts to conquer the big, bad, bald beauty that is Mont Ventoux - one of the toughest and most iconic climbs in cycling.

It was when I was sat on the road, the sun beating down, sweat stinging my eyes, cramp in both legs and my bidon empty, watching as rider after rider passed me, that the enormity of the task I had taken on truly hit me.

I reached into my jersey pocket, pulled out my phone and texted my brother two simple sentences: "The agony never ends. I'm done."

Six months earlier, three friends - Jimbo, Wardy and Steve - and veterans of L'Etape and the Stelvio, had challenged me to join them in the sportive that finished at the summit of Mont Ventoux.

Even then, I had my doubts as to whether I could complete it. I considered myself a good climber - but that was on the short, sharp hills of Surrey, Kent and Sussex. Ventoux is a different beast altogether to Leith Hill or Ditchling Beacon. Twenty-one kilometres and more than 1900 metres of non-stop climbing, the 'Giant of Provence' was way above my pay grade.

French philosopher and cycling fan Roland Barthes described Ventoux...

A god of evil, to which sacrifices must be made. It never forgives weakness and extracts an unfair tribute of suffering.

But, egged on by my brother and my own ego, I prepared to make my offering in the Granfondo New York Mont Ventoux.

Lining up alongside the other members of the 'Ventoux Quatre' at the start line in the picturesque town of Vaison-la-Romaine, the butterflies really kicked in as I looked around at my rivals. I had hoped to see a few dishevelled Frenchmen with overgrown stubble, perhaps with a Gauloise in one hand and a carafe de rouge in the other, but there was not a middle-aged paunch to be seen.

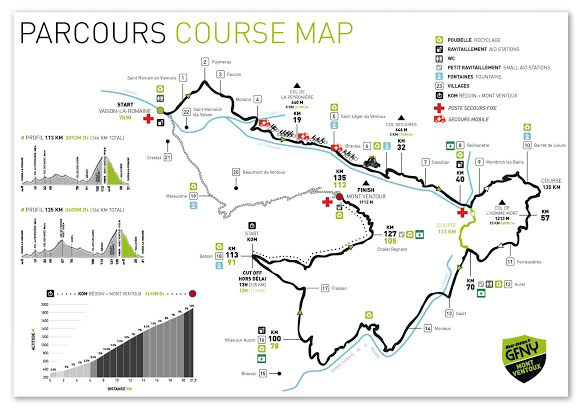

I expected a fast start - and I wasn't to be disappointed. We sped past the Roman amphitheatre and were soon out into the rolling French countryside. The pace was punchy but, with Steve putting in a good shift at the front of our little group, we settled into a steady rhythm for the first two climbs of the day, the Col de la Peyroniere and Col des Aires.

Both were challenging but nothing too horrific - like longer versions of Box Hill - but what they did offer us was some stunning views of the valleys of Provence. It reminded me a lot of the scenery along the Garden Route in South Africa. There wasn't a cloud in the sky but, at this stage, it was still quite cool. That would soon change, though.

Dead Man's Pass

Next up, after about 40km, was the Col de l'Homme Mort - Dead Man's Pass - and if the name itself didn't scare you, the length of the climb would, at 14km.

It was here that I decided to make my attack. I felt strong, my legs felt fine and the gradient seemed easy. I felt so comfortable that I committed the cardinal sin of texting my brother while I was still riding.

I reached the top and was buzzing. Ventoux wasn't that much steeper and just seven kilometres longer. I could handle that, I thought. Pas de problème.

The descent from the Col de l'Homme Mort towards Ventoux through the Gorges de la Nesque is nothing short of spectacular - by far the most beautiful scenery I've ever seen while out on a bike. You weave through gorges, tunnels, hillsides and fields of lavender at breakneck speed but the road surface is immaculate and you never feel in danger of crashing. And this coming from a man who is usually a total coward when it comes to descending.

Finally, after 113km and barely stopping at the two feed stations (for which I'd pay dearly later) I reached the town of Bedoin, took a right and began the climb to the observatory at the top of Ventoux. I still felt in great shape but things started to unravel in the first three or four kilometres. It was not much more than a false flat but it felt like I was cycling in sand. I was thinking to myself, 'If this is what it's like on the easy part, what will you be like on the tougher sections?'

I needed a morale boost so looked at my phone and there were about 50 messages of support from my family. It was just what the doctor ordered.

Dead man climbing

I hit the village of St Esteve and the next bit will always be seared in my memory. There's a left turn and the road ramps up to about 10% - and that's how it stays for kilometre after kilometre after kilometre.

I had been lucky enough to interview Mark Cavendish a few weeks before the 2015 Tour de France and asked his advice about tackling Ventoux.

I won't lie to you, it's pretty awful. But just remember one thing: it will end. It's a motto I've had throughout my career. At some point, it will end.

It certainly didn't feel that way as I looked at my Garmin and realised that I wasn't yet halfway up the climb and was already running on fumes.

Ventoux is brutal. Awful. Agony. And it never stops. There is never a moment where it eases off, lets you have a minute to recuperate, gives you target to aim for. It just drags onwards and upwards through the Bedoin forest for ever. There's just you, the road and a million flies for company.

First I got cramp in one leg, then the other. It made cycling impossible and I had to suffer the ignominy of stopping and getting off the bike to stretch.

That was when I hit my low point and just sat on the road. I was exhausted and there was still about 15km to go. Suddenly, I heard Wardy's voice. "You OK, Andy?" "No. I'm finished" was all I could manage in reply.

Wardy glided past and I thought that would be the last I saw of him. I disconsolately got back on the bike and, pedalling square, weaved across the road to try to gain some momentum.

Five hundred metres later, I see a familiar figure by the roadside. It's Wardy, suffering from cramp in his hamstring. I don't stop though. If I do, I might never start again. Plus, it's every man for himself now, locked in their own personal battle with Ventoux.

Crawling up the mountain at a pace a snail would be disgusted at, disaster then strikes as I realise I'm out of water. In the 36-degree heat, I was sweating buckets, so I was forced to beg a bystander for "un peu de l'eau s'il vous plait!" Never has a bottle of sparkling water tasted so good.

Assault on Chalet Reynard

After what seemed like an eternity spent in hell with the "god of evil", the trees thin out and standing before you is the paradise of Chalet Reynard, the final feed station, about 6km from the summit.

Wardy follows me in a couple of minutes later and tries to engage in conversation but I can't speak. Instead, I pour a bottle of water over my head and, seeing that a van has its boot open, I crawl inside and curl up in the foetal position.

After a few minutes, I emerge and begin filling my face with ginger cake, biscuits, energy bars - anything and everything I can lay my mitts on. Wardy, ever the enthusiast to my curmudgeon, just said: "Fancy a quick 6km spin to the top?" And off we went.

From Chalet Reynard onwards, the landscape is the familiar bleached-white 'lunar' vista that you may have seen in the Tour de France. For the next couple of kilometres I didn't feel too bad and managed to distance Wardy. To be fair, he probably didn't realise he was in a race...

But then the road ramps up again and it's another case of just grinding it out. The observatory looks so close, you feel you can almost touch it. Yet however hard you pedal, it stays resolutely out of reach.

I thought about stopping - again - but with the messages flooding in from my wife, brother, sister and mum, I knew I had to dig in. The quicker I got up there, the quicker the pain would end.

I'd love to say I stopped at the memorial to British cyclist Tom Simpson, who died on Ventoux during the 1967 Tour de France, and left my bidon there as a mark of respect. But, in truth, I just wanted to finish, so I resorted to bowing my head as I went past.

The last 2k nearly broke me but I remembered a text my brother sent me before I flew out to France. "If you come last out of your mates, don't bother coming home." It was meant in jest - I think - but those words resonated with me and I ploughed on, taking the final, steep right turn with a smile on my face and my heart pounding through my chest.

I crossed the finish line and didn't have to wait long for Wardy. We hugged then went our separate ways so we could each have a 'moment'. I phoned all my family and couldn't hold back the tears - I was a physical and emotional wreck.

Steve - who was actually the fastest of us to climb Ventoux itself - and Jimbo soon joined us and we lay around, enjoying the view and trying to take in what we'd all achieved.

There's no denying it, Mont Ventoux is frighteningly tough. It's a nasty, unrelenting climb and it will take you to the darkest of places.

But if you can handle everything it has to throw at you and you can conquer Ventoux, it will live with you for ever and be right up there with the most amazing achievements of your life. It certainly was for me.

The other brother

Separation anxiety. As the date approached, a certain wistfulness came over me. When I learned they were hiring a black van with sliding doors to transport their bike boxes, wistfulness turned to envy. It felt like the A-team was going off on a mission without breaking Murdoch out of the asylum.

The parting gift was my Garmin. He faithfully promised to follow my instructions. GPS for Luddites.

The day of the ride I was up and logged on early. Watching a dot jag across a map can be surprisingly compulsive viewing. For those of a certain age (that's 80% of amateur road cyclists) it's kind of like trying to follow a football match on Ceefax.

In a show of solidarity, I set out on a solo ride. Out to Westerham and up the north face of Toys Hill. Checking progress at every opportunity, texting encouragement, living every pedal stroke vicariously. Ven-toux, ven-toux, ven-toux, ven-toux.

The joking turned to genuine concern when I got his final, despondent text, some distance from the summit. I feared a DNF. But on reaching the peak of Anerley Hill, felt a welcome buzz from my back pocket. The boy had done it. Vent-who?

Check out our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter @broleurcc