What makes a hill climb hard?

Most of the cycling climbs in the UK are best described using the words of the English philosopher, Hobbes: "solitary, nasty, brutish and short". But what makes some hills more nasty and brutish than others?

Shouldn't take long

Just multiply the gradient by the distance, factor in the surface quality and the weather, add the weight and fitness of the rider and subtract the state they're in when attempting the climb. Easy.

I could stop there, unclip and call it a day, but I'm not going to. I'm digging deeper. Going harder and stronger, for longer. Are you with me? Saddle up.

What exactly is a hill?

Asked nobody, ever. Perhaps the better question is: when does a hill become a mountain? I could show you a picture and you'd intuitively know which you were looking at. Mountains are pointy (unless they're Table Top mountain, or Sugar Loaf mountain) and hills are roundy. Mountains are steep, sometimes sheer, with stony faces – like Mount Rushmore. Hills less so. Mountains soar majestically beyond the clouds. Hills just sit there, lumpen.

Let's get scientific, or rather, geographic. According to the US Geological Survey, there is no difference between hills and mountains. Fake news – I blame Trump. Here in Britain, we're smarter than that. Until the 1920s, the British Ordnance Survey defined a mountain as a geographic feature rising higher than 1,000 feet (304 metres). We set a bar – and then for some reason in the 1970s we decided to raise it. The Oxford English Dictionary now says anything up to 600 metres above sea level remains a mere hill.

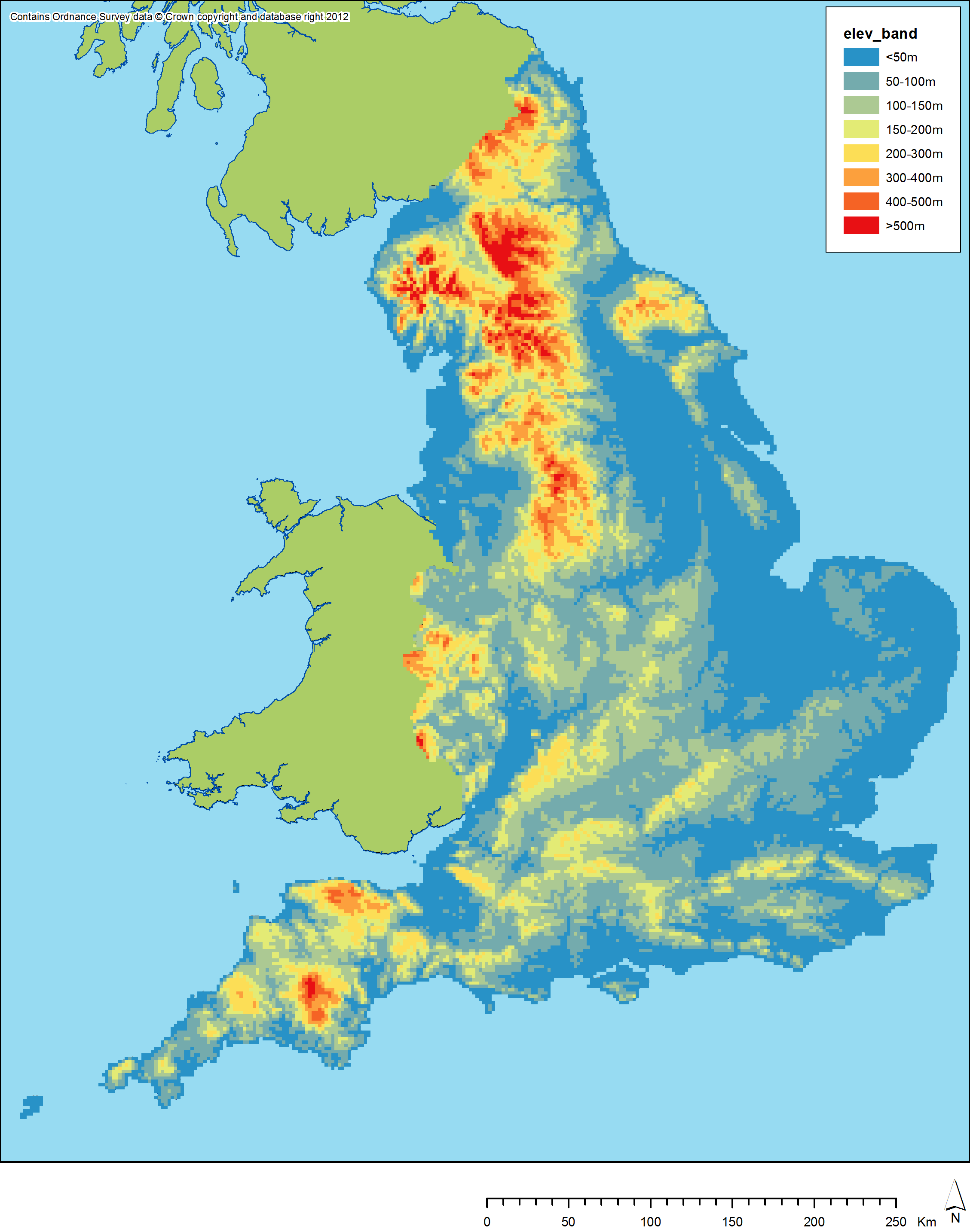

Looking at this map of England (sorry, couldn't find one covering the whole of the UK), it's safe to say that if you live anywhere south or east of Wigan, you're not cycling up mountains. Those orange peaks in the Peak District – hills.

What compels people to climb hills?

There are the flat track bullies who, in the words of one followeur, "avoid hills like herpes", fearful of bringing their average speed down. Racing (not riding) fast laps of Regent's Park or indulging in a "bun run" to Windsor's Cinnamon Café (recommended). However, most semi-serious cyclists actively seek out climbs. And when they've ticked off the easy ones, they cast around for something harder. This phenomenon is best evidenced by the enduring popularity of our lists of the top ten toughest hill climbs of Kent, Surrey, Sussex, London and the Chilterns. There's a recessive Cub Scout or Brownie gene in all of us. More badges to be sewn on the sleeve. More flair for the lanyard.

When asked why he wanted to climb Everest, George Mallory famously replied "Because it's there." Ask cyclists why they want to climb a hill now and the answer could well be, "Because it's on Strava".

Previously you'd have to wait a year for your local cycling club's hill climb competition to test yourself against others. Now you can do it on any climb, every day of the week, comparing yourself to friends, followers and riders of the same age and weight (if you're prepared to pay the premium). Only going uphill, mind. After a series of accidents involving segment-chasers in the litigious US, Strava made it impossible to create segments on descents.

We also compete against ourselves of course. Few things are more addictive than the thrill of self-improvement. New PRs have become the opium of the two-wheeled masses. To paraphrase Greg Lemond, the climbs don't get any easier, you just go faster up them. And Strava is how you know.

Man vs hill

Ever heard of anthropomorphism? If you've named your bike, you may be a sufferer. Actually, we all have a natural tendency to ascribe human traits, emotions, or intentions to inanimate objects. You're not weird after all.

Thus we measure ourselves (humans) against hills (things). And there's a pecking order. We know the ones we've got the better of – and the ones that always seem to hold the upper hand. I've come across some very nice, gentle hills. I've also encountered some downright nasty, vindictive bastards. Sometimes, it gets personal. Boltby Bank in Yorkshire, for example. Let's just say there's a score to be settled.

Everyone needs a nemesis, but there's always some people take their vendettas a step too far. Why climb Everest when you can Everest a climb? In 2020, Everesting – repeating the same hill until a total of 8,848 metres have been ascended – became a thing.

I personally prefer my concept of Struggling a climb: riding the 403 metres equivalent to the elevation gain of the Kirkstone Pass (better known as 'the Struggle'). It's so much more descriptive – not to mention easier – but for some reason it hasn't caught on. You can use our Everesting Calculator to enter the stats for a climb to see how many times you'd need to ride up it to Everest – and how fast you'd need to go to nab a world record. (To do it on Box Hill you'd need to average 48.6 kph!

Classifying hill climbs

Probably the most famous list of hills to ride up is Simon Warren's 100 Greatest Cycling Climbs, or the inventively named sequel: Another 100 Greatest Cycling Climbs. Interestingly, he makes no attempt to subjectively rank or classify them. Probably due to the little-known but widely-experienced condition called climbnesia, or hill blindness, where utter exhaustion can make one grim ascent feel much like another and they eventually merge into a single Frankenclimb.

Strava, on the other hand, does.

"Our categorisation is completely objective, so if a climb is Cat 1 it will always be a Cat 1 climb. To decide the category of a climb we multiply the length of the climb (in meters) with the grade of the climb in percent."

For a hill to be classed as a categorised climb, the total score must be 8000 or more and it must have a minimum gradient of 3%.

- Cat 4: >8,000 points

- Cat 3: >16,000 points

- Cat 2: >32,000 points

- Cat 1: >64,000 points

- HC: >80,000 points

To reach 600m (the height of a mountain in the UK, if you haven't been paying attention), you'd have to climb for 20 kilometres from sea level at a steady gradient of 3% – that would be a score of 60,000.

To further contextualise this with some famous UK climbs, let's look at the rather benign Box Hill in Surrey, Winnats Pass in the Peak District, venue for the 2021 National Hill Climb Championships, and Hardknott Pass in the Lake District, arguably the toughest hill climb in England.

- Box Hill: 2280 metres x 5.2% gradient = 11,856 points – Cat 4

- Winnats Pass: 1710 metres x 11.2% gradient = 19,152 points – Cat 3

- Hardknott Pass: 2230 metres x 13.3% gradient = 29,659 points – Cat 3

In theory, this classification makes sense, a simple formula that enables the objective comparison of any two climbs. In reality, it's deeply flawed in terms of assessing how hard a hill actually is. Consider York's Hill in Kent. It's only 640m long and with a gradient of 12.8% it scores 8,192 points on Strava's scale, barely scraping a Cat 4 classification. Nobody, but nobody, can tell me that Box Hill is harder to ride up than York's.

Average gradients can be misleading. Very few climbs in the UK have a consistent gradient from start to finish. Some have flat sections. Some, like Whitedown in Surrey, include dips or descents. Others, like the Downerberg in Kent ramp up horribly at the finish.

Maybe the maximum gradient is a better indicator of how hard a climb is to ride? Beyond 15% you're going to lose all forward momentum. Anything over 20% you're going to struggle to stay in the saddle. Up above 25% and without the right gearing, it may be a challenge to stay on the bike (grrr... I'll get you Boltby).

It's not all about the gradient

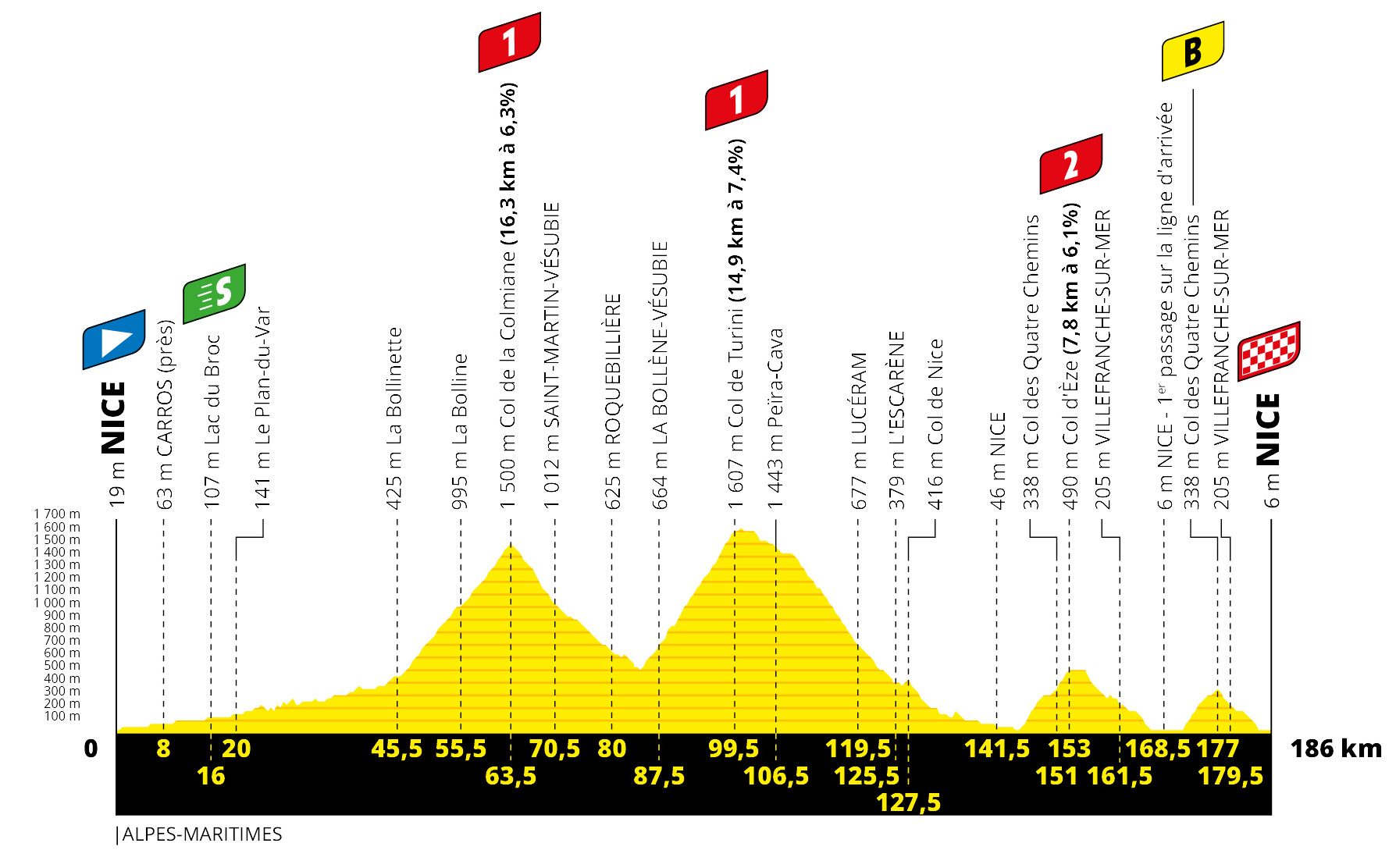

In the Tour de France – as on Strava – the climbs are classified into categories from 1 to 4 based on their difficulty. This is rumoured to be based on the gear a Citroën 2CV would need to be in to get up the hill: first gear for the steepest climbs, fourth gear for the easiest, with those beyond the power of the two-stroke engine classified as hors catégorie, or "beyond categorisation".

However, as well as taking into account the gradient and length of the climb, the race commissaires also consider the location of the climb within the stage (near the start or end), and its location in the overall race (early in the race or toward the end). Thus the same climb could, in theory, be classified differently from one tour to the next.

This makes sense. Attacking a hill early in a ride when fresh is a totally different proposition to facing a climb at the very end of a long day in the saddle. Wrapping up our Sunday rides in Kent with an assault on Anerley Hill in Crystal Palace often felt like a summit finish on the Mortirolo. Repeated punchy climbs can be way more fatiguing than one long ascent. I found the sawtooth parcours of the Tour of the Hills Audax way more challenging than the marathon 32 km climb up Teide in Tenerife.

Come and have a go...

The state of your bike can have as much of an influence as the state of your legs. Nobody wants to take on Hardknott sporting a 53/39 chainset. Ever tried climbing a hill with a slipping chain? Nightmare. Even a bit of rust on the drivetrain can reduce the efficiency of your power transfer, make life that tiny bit harder.

Then there's the road surface to consider. One of the things that adds to the challenge of York's Hill in Kent is the shocking state of the road, especially after a downpour. (I can hear the mountain bikers' mocking sniggers from here). Stand up in the pedals and you risk the back wheel spinning out, sit too far back and the front wheel is lifting. And that's nothing compared to the cobbles of the Koppenberg or Kwaremont in Flanders where a bit of rain can make the surface greasily treacherous (thankfully, there's no notable hills on the Paris-Roubaix Challenge).

Which brings us to the weather. There's little to like about riding uphill in driving rain, while pedalling squares into a headwind is downright miserable – like swimming in one of those hotel pools with a jetstream counter current (I'd imagine). I'm not sure I've ever ridden with a tailwind up certain hills like Staple Lane in Surrey or Sawyers Hill in Richmond Park. Just spare a thought for those attempting to join the Club des Cinglés du Mont Ventoux a couple of weeks ago when wind speeds over 320 kph were recorded.

Almost as bad as being exposed to the elements is being hemmed in by a claustrophobic canopy of trees, like on the Mortirolo, or its Surrey stepbrother, Whitedown. I'm not sure what's worse: cars flying past at speed on a busy road, wing mirrors clipping your elbows, or impatiently revving their engines behind you on a narrow lane.

How to get better at hill climbing

The bitter irony of typing out that sub-head is not lost on me. But to those thinking "Steve, you're a hopeless climber", you have absolutely no idea just how bad I once was. Besides, this isn't about being good, it's about improving. The lower the base, the higher you can go.

Being of the same height and weight (6'2" and 80-90 kilos, depending on the time of year), neither Andy or I are built for riding up hills on bikes. Let's just say we're much better suited to quickly picking up momentum down them. I tend to stay planted in the saddle, he's immediately up in the pedals, but both of us are generally fighting a losing battle with the Big G – gravity.

Once your speed drops below 16kph – which won't be long on any climb of substance – gravity is far and away the biggest source of resistance. In that sense, any cycling climb is truly a battle against yourself. The easiest way to start dropping people on hills? Drop some excess baggage.

We have a friend James, who typically weighs in around 58 kilos. We rarely see anything but the back of him on climbs. Thankfully, he takes lots of selfies so we know what he looks like. He'd have to be carrying a fully-packed 23 kilo suitcase – that's the maximum weight for check-in on British Airways – plus hand luggage, to get close to what we have to carry in excess midriff.

If, like us, you weigh 85 kilos and your fully-loaded bike weighs 8.5, then the bike is only 10% of your overall mass. It's a myth that you can buy speed, you have to earn it. Yes, you could go shopping for carbon fibre cages, drill holes in your gear levers and remove your bar tape. Alternatively, you could forsake the pies and cake. (Nobody said this was going to be easy).

Other hill climbing tips and tricks

If a diet of alfafa sprouts and mung beans doesn't appeal, the other way to improve your hill-climbing prowess is to generate more power. Unfortunately, that means training (or trying a bit harder). Riding up hills lots is ideal. You can check out our top 15 training tips for beginners here, or if you want to see exactly how many additional watts you need to output in order to hit a target time, use our Hill Climb Calculator.

Scouring the interweb so you don't have to, we've unearthed the following additional recommendations:

- Top up your energy levels. For solid foods like bars or bananas - at least 15 minutes before the start, for sugary foods like gels or jelly babies, a couple of minutes should be enough

- Empty your bidons (as long as there's a tap at the top). A litre of water weighs a kilo - instant weight loss!

- Stay supple and relaxed. Think Zen thoughts and imagine you are light, like a floating cloud or a soaring kite

- Breathe deep and take in oxygen. Open up your chest by lifting your head and placing your hands wide on the hoods

- Spinning is winning. A quicker cadence is ultimately less tiring than grinding - but ultimately do what feels right for you

- Use your upper body. Pull back on the bars to give yourself a bit of leverage

- Don't go out too fast. Try and hold something back for the last third of the climb if you can, then flog yourself

In manibus ignem

The Broleur motto, In manibus ignem, roughly translates as "hands in the fire". It was inspired by a great piece on Chris Froome in Esquire, The Hardest Road, written by Richard Moore. In it, Froome talks about the psychological side of cycling, as well as the physical.

“It’s about the body only up to a certain point. There comes a point when you’re both so far into the red and so far over your limit that it turns mental; it’s a mental game. It’s like you both have your hands in the fire and the first to pull out loses.”

Just as beauty is in the eye of the beholder, difficulty is in the mind of the climber. The head invariably goes before the legs. Next time you're feeling the burn, just remember, all you have to do is keep your hand in the fire for a few seconds, minutes or heaven-forbid, hours more. As Sir Edmund Hillary once said,

“It's not the mountains we conquer, but ourselves.”